by Donald L. Ross, DVM, MS, Diplomat, ACVD

Occlusion

The normal or correct occlusal pattern of the dog is most often referred to as a “scissor bite” in the AKC breed standards. However, few (if any) of these standards go further than describing the relationship of the incisors or stating the number of teeth that should be present. This limited definition is of minimal value in actually describing the canine occlusion or for planning breeding programs.

The final occlusal pattern of the dog is the result of two major factors — the genetics of the individual and the physical forces exerted by the interlocking action of the upper and lower teeth during growth. Genetics includes not only the inheritance of the size and shape of the bones of the face and the teeth but also the factors controlling the timing of the development of the deciduous (baby) teeth, the resorption of the deciduous roots, and the eruptive pathway of the permanent teeth. The mechanical forces generated by the upper and lower teeth during the first few months of life are a major factor in coordinating the growth of the face. The genetic and mechanical forces can act to accentuate, modify or reverse each other as the body grows.

Because the phenotype (appearance) of each dog’s bite structure is all we have to base decisions relating to its oral health and breeding potential, it is essential that we use as many observations or evaluation points as possible. The position of the incisor teeth is the easiest to see but the positions of the canine and premolar teeth plus the relationship of the tempro-mandibular joint to the angle of the mandible consistently provide critical information.

Types of Occlusion

Using the terms standard in defining human occlusion, there are four types or classes of occlusion. These occlusal classes are defined as if the upper jaw is normal and relates evaluation to the accompanying position of the lower jaw. The classes areNormal (see the six structural definitions below)

- Normal but with missing or rotated teeth

- Brachygnathic (overshot or longer upper jaw)

- Prognathic (undershot or longer lower jaw)

Each of the abnormal types can have subcategories. However, for the our basic evaluations, it is adequate to just consider the severity of changes in the five structures listed below:

Incisors – the maxillary or upper incisors are positioned in front of the mandibular or lower incisors with the upper incisor tips covering the front surface of the lower teeth. The upper central incisors directly overlap the lower centrals. The upper intermediate and lateral incisors are positioned to contact the interproximal sites between the lower incisors. The midlines of the upper and lower jaw must be in vertical alignment.

Incisors – the maxillary or upper incisors are positioned in front of the mandibular or lower incisors with the upper incisor tips covering the front surface of the lower teeth. The upper central incisors directly overlap the lower centrals. The upper intermediate and lateral incisors are positioned to contact the interproximal sites between the lower incisors. The midlines of the upper and lower jaw must be in vertical alignment.

Canines – the lower canine teeth occlude between the upper canine and the upper lateral (3rd) incisor. Any shift, so that the lower canine contacts either of the upper teeth, is a degree of an abnormality. Additional severity of the defect would be if the lower canine wears against either upper tooth. A very strong defect would be indicated by the lower canine tooth occluding behind the upper or in front of the upper incisors.

Canines – the lower canine teeth occlude between the upper canine and the upper lateral (3rd) incisor. Any shift, so that the lower canine contacts either of the upper teeth, is a degree of an abnormality. Additional severity of the defect would be if the lower canine wears against either upper tooth. A very strong defect would be indicated by the lower canine tooth occluding behind the upper or in front of the upper incisors.

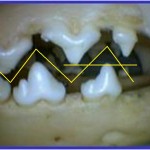

Premolars – the large cusp tip of each of the lower premolars should point directly into the space in front of the upper premolar of the same name and overlap the cusp tips of the opposing arch at least as far forward as the 2nd premolars. When the large cusp tip of a lower premolar points toward any part of an upper

Premolars – the large cusp tip of each of the lower premolars should point directly into the space in front of the upper premolar of the same name and overlap the cusp tips of the opposing arch at least as far forward as the 2nd premolars. When the large cusp tip of a lower premolar points toward any part of an upper  premolar tooth, it must be considered an abnormality. When the mouth is closed, the premolars should look like the teeth of pinking-sheer scissors. Any increase in the space between the upper and lower cusp tips indicates a ventral bowing of the mandible that is necessary to accommodate excessive mandibular length.

premolar tooth, it must be considered an abnormality. When the mouth is closed, the premolars should look like the teeth of pinking-sheer scissors. Any increase in the space between the upper and lower cusp tips indicates a ventral bowing of the mandible that is necessary to accommodate excessive mandibular length.

The angle of the mandible as it relates to the TMJ – the caudal edge of the angle of the mandible should be directly below the tempro-mandibular joint. If the angle of the mandible is caudal to the TMJ, the mandible is too long (prognathic or under shot). If the angle is forward of the TMJ, the mandible is too short (brachygnathic or over shot). If the mandible lacks normal length in the incisor area, it is typically deficient in length at the angle of the mandible. If it has excessive length in the incisor area, there is typically excessive length at the angle of the mandible.

The angle of the mandible as it relates to the TMJ – the caudal edge of the angle of the mandible should be directly below the tempro-mandibular joint. If the angle of the mandible is caudal to the TMJ, the mandible is too long (prognathic or under shot). If the angle is forward of the TMJ, the mandible is too short (brachygnathic or over shot). If the mandible lacks normal length in the incisor area, it is typically deficient in length at the angle of the mandible. If it has excessive length in the incisor area, there is typically excessive length at the angle of the mandible.

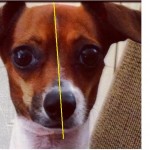

The midline of the head – starting with the occipital crest (top/back point of the skull), the midpoint between the eyes, the midline of the nose pad and the midline of both the upper and lower arches should lie in a straight line (the same vertical plane). Variation from this alignment of the skull forms the basis of the “wry” bite abnormality.

The midline of the head – starting with the occipital crest (top/back point of the skull), the midpoint between the eyes, the midline of the nose pad and the midline of both the upper and lower arches should lie in a straight line (the same vertical plane). Variation from this alignment of the skull forms the basis of the “wry” bite abnormality.

Right Side Defects vs. Left Side Defects (Wry-bite)

Just as the genetics of the upper jaw are separate from those of the lower jaw, the genetics of the right side of the face are separate from those of the left side. As mentioned above, the mid-line points of the head all should lie along the same vertical plane. In this evaluation, the occipital crest and the mid-point between the eyes form the basis of the skull structures. Then the same line or plane should extend forward to the mid-line of the nose pad and the mid-line of both the upper and lower dental arches (the facial bones). More simply, all of these points should be in a straight line. When any of the points at the front of the face aren’t positioned along the basic midline of the skull, the resulting abnormal occlusions are called a “wry” bite.

In common usage, the term “wry” bite has been expanded to include any right side vs. left side abnormality. One of the common abnormalities seen is the unequal development of the two bones that house the roots of the upper incisors. Similar variations in the rostoral mandibles also exist. Not much work has been done to study this small group of abnormalities but it is reasonable to just include these in the “wry” group of abnormalities. No easily applied criteria are available for a definitive discussion. When judging the potential impact on future generations, it seems safer to include them in the “wry’ group than to ignore them because of not having a solid understanding these problems.

The Genetics of Occlusion

In very general terms, the structure of the face tends to be passed on as an “additive” inheritance pattern rather than just a simple dominant or recessive pattern. Therefore, if both parents have a slightly ‘long’ lower jaw, the offspring will potentially be worse than either parent. If a ‘long’ individual is bred to a ‘short’ individual, the majority of the offspring will be somewhere in the middle.

It is also noteworthy to mention that the general size of the teeth, as compared to the space available in the bone for the teeth, can result in occlusal problems. In a breeding program, it is much easier to change bone size than to change tooth size. This factor is responsible for the crowding and rotation problems in many of the smaller breeds. It also helps explain the greater incidence of periodontal disease and early tooth loss in the smaller breeds. Those breeds that have changed the head shape toward a more refined, tapered face are now seeing an increase in orthodontic problems because they haven’t been able to effect a corresponding change in tooth size as compared to the changes in the facial bones. Correction of this genetic factor can’t be achieved in just a few generations. It is possible that as many as 50 to 1000 generations will be needed in their breeding programs to achieve a proportional change in tooth size. The total arch length must be maintained in any planned changes in the facial bone or the structural (orthodontic and periodontal) problems of the breed will become a serious problem.

A final point! The bones of the face don’t develop like those of the arm or leg. They enlarge much like a balloon; they start small and enlarged in all directions, as predetermined by genetics, to give the final form. If a balloon is shaped like a baby duck, it will look like a duck whether it is empty or full of air. If an outside physical factor is introduced during ‘growth’, like a wall, the beak may be blocked from normal ‘growth’ but the rest of the balloon expands slightly more to accept the same total volume of air. If the rostoral mandible is blocked from expansion by the position of the teeth, the middle and back areas of the mandible will deform to accommodate the growth process. We don’t understand all the components of genetics and the development of abnormalities. However, we must expand the evaluation of the mouth beyond just the number of teeth present and the position of the small incisor teeth!

|