Then and Now

by C.A. Sharp

First published in Double Helix Network News, Summer 2006, Rev. My 2013

In the mid-1980s Australian Shepherd breeders became aware that Collie Eye Anomaly (CEA) was a factor in the breed. CEA is not the most serious eye disease in our breed or the most common, but it does require breeder awareness and, when diagnosed, a plan of action.

Historical Perspective

Little was know about Aussie CEA in the 1980s. The disease was well documented in Collies, for whom it was named, and was also known in Shetland Sheepdogs. At first, no one was certain whether the disease observed in Aussies was the same, beyond its appearance. When asked by concerned Aussie owners and breeders, more than a few veterinary ophthalmologists would flatly declare “that doesn’t happen in your breed!”

At the time CEA was gaining recognition among breeders, ASCA had a Genetics Committee. Committee structure was very different in those early days and the Genetics Committee consisted of two people: Chairman Betty Nelson and me. We had been receiving reports about CEA and had tried to do our homework, but all the available veterinary literature concerned Collies. No one had looked at the condition in Aussies. We started writing about CEA in our regular Aussie Times column and requested that members with affected dogs share their information with us.

In 1984 a breeder made the unhappy discovery that two puppies in her litter had CEA. Her vet, Alan McMillan of San Diego, was the ophthalmology consultant to ASCA’s committee. The breeder was soon in touch with us and asked if we would like the affected puppies. We agreed and the two black tri pups, I dubbed Tweedledee and Tweedledum because they looked so much alike, came to live with me.

The breeder was very open about what had happened and even wrote a short piece for the Aussie Times about her experience. Unfortunately, that triggered the same kind of circle-the-wagons/shoot-to-kill reaction from some of her fellows that we have seen more recently in connection with epilepsy. One person, in a letter to the Times, excoriated her for having neutered her carrier stud dog and placed him in a pet home, implying that she had been cruel to treat the dog this way!

By the time we received Dee and Dum, the Committee had gathered enough information to indicate that Aussie CEA was likely a recessive, as it is in Collies and Shelties. In order to prove that point, we bred Dee and Dum together when they were old enough. All of their puppies were affected, proving that CEA was also recessive in Aussies.

We did several additional matings. Dum, the affected male, was bred to the daughter of a then-popular stud suspected of being a carrier. The daughter, my own Moby of Didgeridu, proved to be a carrier: Three of her seven pups were affected. We also bred Moby to a dog whose pedigree indicated he was unlikely to be a carrier. All those puppies were normal. One of the daughters from that litter, Lockwood’s Tucker of Dragonwyre, was also bred to Dum and proved to be a carrier herself. Most the affected offspring in these litters had choroidal hypoplasia. A few also had unilateral optic disc colobomas. One puppy out of Tucker’s litter was totally blind due to retinal detachment.

During this period, the Genetics Committee was disbanded. Betty and I knew we were on to something with CEA. We continued work on our own, gathering pedigrees and eye exam forms on affected dogs. This effort was important, but what we really needed was a researcher willing to review the data and write a journal article about it. An article published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal is the only way to make something “real” to a doubting veterinary community.

We searched for several years without success. Researchers we approached either had too many other projects already or this one wasn’t quite in their area. Finally, Dr. MacMillan suggested we try Dr. Lionel Rubin, author of Inherited Eye Diseases in Purebred Dogs. Dr. Rubin agreed to look at what we had. We organized the pedigrees and eye exam sheets, created genealogy charts that indicated interrelationships among the pedigrees, and sent them off. After reviewing the information, Dr. Rubin agreed that CEA was recessive in Aussies and the same disease observed in Collies and Shelties.

Ultimately, “Collie eye anomaly in Australian shepherd dogs,” by Rubin, Nelson and Sharp, appeared in the Journal of Veterinary and Comparative Ophthalmology. The publication provoked an editorial that appeared in the same issue of the journal from one of Dr. Rubin’s colleagues, arguing that the disease should not be called Collie Eye Anomaly, but Australian Shepherd Eye Anomaly. Dr. Rubin responded with a rebutting editorial titled “A Rose By Any Other Name.” While most veterinary ophthalmologists soon recognized that CEA was a factor in Aussies, there were still a few hold-outs over the next dozen years or so who would not agree that the disease was present in the breed. When I learned of such individuals, I mailed them a copy of the article.

Managing the CEA Crisis

CEA was relatively common in the 1980s, quite possibly more common than our current #1 eye disease, cataract. General recognition that CEA is recessive helped breeders deal with it, though most still kept information secret from their fellow breeders.

To aid in breeder education, I developed one-page informational handout modeled on one developed by the Morris Animal Foundation for Combined Immunodeficiency Disorder, a recessive disease in Arabian Horses. MAF graciously granted me permission to do so. Breeding program management of a recessive disease that can be identified in very young animals is the essentially same whatever the species.

I started doing pedigree analysis, for CEA only, in the early 1990s. I used the research data and additional information that was subsequently shared by breeders and owners. I included the CEA handout as an educational insert with the analysis results. I also distributed it at my seminars and when people contacted me with questions about CEA or eye disease in general. It’s been revised as necessary to encompass up-to-date information and the current version of it can be found on the ASHGI website.

Meanwhile, a group of Northern California breeders struggling with CEA in their lines decided they needed to do something. I worked with them to develop a test-breeding program. They created an excellent set of forms to document the breeding, the litter itself, and the exam results on the pups. These breeders also took a public stand.

As a group, they purchased a full-page ad in the Aussie Times, signed by all of them, titled “For Your Eyes Only.” They jointly admitted they had produced CEA and listed the names of their carrier dogs. While the ad generated considerable muttering, none of them received the sort of direct attack experienced by the breeder of Dee and Dum. This pubic action from a unified group discouraged attempts by “Incorrigibles” (those who actively and aggressively try to suppress genetic disease information) to shove CEA back in the closet. In a subsequent ad, the group told about the test-breeding they had done to clear their stock.

These good people proved invaluable in another way. When people contact me about a genetic problem in their Aussie, I’m “the expert,” not a kindred spirit. A lot of folks I spoke to were suffering varying degrees of emotional distress. I called upon the “For Your Eyes Only” breeders to serve as a support group to these people. Once again, they came through. Their efforts foreshadowed the more recent “EpiGenes” discussion list, which offers information and support for breeders dealing with epilepsy and other more serious hereditary issues in Aussies.

Finding the Gene

In the mid-1990s, Dr. Gregory Acland of Cornell University started his ultimately successful search for the CEA gene. Most of his data came from working Border Collies. T American Border Collie Association, the working Border Collie club, provided the majority of the necessary funding. Acland contacted all the US clubs for breeds affected with CEA, but only the ABCA came through.

Early on, Acland established via test breeding that the disease was the same in Border Collies and Collies. Participation by the Australian Shepherd community was minimal, even though the study was publicized on the discussion lists and in the Times. One breeder, Cully Ray, provided a substantial donation and a few people offered CEA- affected Aussies. One person did so in the face of negative breeder reaction that came close to stalking. This little bit of assistance from a few dedicated and determined individuals allowed Acland to make the mating that determined the disease was the same in Aussies.

Ultimately he discovered that the recessive nature of the disease is due to a single gene of major effect that causes choroidal hypoplasia, the primary CEA defect. Acland had been suspicious this might be the case because Collie breeders, who have dealt with extremely high incidence of this disease in their breed for decades, had selected away from the most severe forms. Most Collies still have CEA, but very few have serious vision loss.

The more serious CEA defects, optic nerve coloboma and retinal detachment, are governed by as-yet unidentified genes. The good news for breeders is that the choroidal hypoplasia gene is key. Without two mutated copies of that, the dog will not have CEA. The disease can still be managed like a single-gene recessive even though it is multi-gene. A commercial DNA screening test is now available.

Breeder Management of CEA

The good news is that CEA is no longer common in Aussies. Fewer than half a percent of dogs are affected, which indicates that around 5% are carriers. This still means that one out of twenty dogs has at least one copy of the mutation. That is frequent enough that breeders need to be aware of it.

With these numbers, DNA testing every individual isn’t necessary. Knowledge about the disease and when to utilize both the DNA test and traditional veterinary eye exams will enable breeders to deal effectively with CEA should it occur in their breeding programs. With a little effort on our part, we can reduce the frequency of the mutation to even lower levels.

CEA is present at birth, so affected puppies will be identified during a puppy eye exam. It is important that all Aussie puppies be checked. Typically, around one in four pups in an affected litter will have CEA. If only the ones that are going to show or breeding homes are examined, affected puppies may go unidentified. Two thirds of the normal littermates will be carriers, so it is very important to know whether or not CEA is present in any given litter.

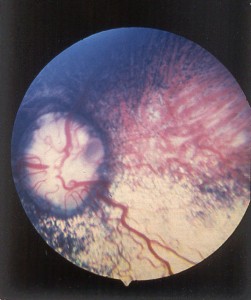

Choroidal hypoplasia (CH,) the most common CEA defect, is present in all affected dogs. Most do not have the more serious optic nerve coloboma or retinal detachment. It is vital that puppies be checked as young as possible because the CH may not be visible to the examiner once the tapetal pigment (reflecting layer used for night vision) fills in. This was once referred to as the “go-normal phenomenon,” but the dogs are not actually normal. However, these dogs are not normal and a better term is “masked affected.” If the eye were removed, sectioned and examined under a microscope the defects would still be visible. This is totally impractical as a diagnostic tool for obvious reasons. Because of the risk of masked affecteds, breeders should do everything in their power to get the puppies examined between five and seven weeks of age. The later the pups are examined, the greater the risk that CEA-affected puppies might go undiagnosed.

If a dog has CEA, both of its parents will be carriers. There is no need to DNA test them. The grandparents, normal full- or half-siblings of the affected dog and full siblings of the parents should be DNA tested if they are to be used for breeding in order to determine their CEA status. Non-breeding dogs do not require a DNA test. When a relative is found to have the CEA mutation, its first step relatives (parents, offspring and full siblings) should also be tested if they are intended for breeding. The process should be continued as additional CEA individuals are identified.

The parents of a CEA puppy and any dogs that are DNA tested and found to be carriers should only be bred to dogs that have been DNA tested clear of the CEA mutation. Subsequently, all puppies from identified carriers should be DNA tested for CEA if they will be used for breeding. Ideally, any male offered at public stud should be tested, unless both parents previously tested clear of the mutation.

The DNA test can also be used to verify or reverse a diagnosis made via a standard eye examination. Veterinary ophthalmologists are highly trained specialists, but any physical exam is by nature subjective. Errors and misjudgments will occur, though the incidence is low. A breeder once contacted me about one of her dogs being diagnosed with CEA. The dog had been given two clear eye exams previously by other vets. In addition, the pedigree was not one in which I would have expected to find CEA. I advised the breeder that she have the dog DNA tested. He came back clear.

As of 2011, Optigen LLP, which offers the DNA test, had performed 1196 CEA tests on Aussies. Of those, 1% were affected, 15% were carriers, and the balance were clear. While 15% of the dogs tested had at least one copy of the choroidal hypoplasia mutation, it is important to remember that the only dogs likely to be tested are those who are at risk of being carriers. Therefore, the results will be skewed toward carrier dogs. Actual carrier rate may be lower.

Where do we go from here?

CEA is not nearly the problem for Aussie breeders that it once was. In the 1980s a few well-used sires happened to be carriers and for a while CEA was topic-one among our inherited health issues. As knowledge of the recessive inheritance of the disease and awareness of the affected bloodlines spread, breeders were able to deal effectively with the problem, reducing the frequency of CEA.

Many in the breed today aren’t aware that CEA was ever considered a significant issue in Aussies. Because of this ignorance, puppy exams may not be done or, if they are, may be done too late or only on part of a litter. All that is required to make CEA a major breed health issue again is a single popular sire who happens to be a carrier. Our general lack of vigilance on this issue could be setting us up for another round of CEA-affected dogs.

The knowledge and technology are there to prevent this from happening. All that is required is that we have the will to put it to work for us.