by C.A. Sharp

First published in the Aussie Times, Sep-Oct 2011

ASHGI would like to thank the hundreds of Aussie owners who took the time and effort to fill out a very lengthy and detailed survey form, some of them several times. Without their participation in this project, as well as the efforts of our hard-working survey committee volunteers, we would not have been able to collect a large and valuable set of breed health data. We would also like to thank Marja Tegelbeckers for the excellent illustrations of dentition and tail conformation used in the survey and this report.

The Australian Shepherd Health & Genetics Institute, Inc. (ASHGI) conducted its Comprehensive Australian Shepherd Health Survey from August 2009 through August 2010 after a year of planning and preparation by the survey committee. The committee [see Figure 1] included not only ASHGI volunteers but the Health & Genetics Committee chairs of both the Australian Shepherd Club of America (ASCA) and the United States Australian Shepherd Association (USASA) as well as the health liaison for the Australian Shepherd Club of the Netherlands, an FCI club. All three breed clubs will receive a copy of the survey summary data in recognition of their contributions. (All detailed data will remain confidential and in ASHGI’s possession.)

| Fig.1: Survey Committee |

| Committee Chair: C.A. Sharp, Pres. ASHGI Committee Members: |

This was the second major general health survey conducted for the breed. The first, by the ASCA DNA & Genetics Committee (presently the DNA Committee) took place in 1999. A small private effort had previously been offered by Leos Kral, PhD, of West Georgia State University in the late-1990s.

ASHGI contracted with Elements Software Engineering, LLP (ESE) of Hurley, Wisconsin for technical support based on ESE’s experience in programming breed health surveys and the good reports received from prior clients. ESE’s principal, Larry M. Hopkins, programmed and hosted the web version of the survey and stored the data on his server while the survey was operational.

ASHGI prepared electronic and paper versions of the survey form for those who did not wish or were unable to utilize the web-mounted version. Responses submitted by electronic copy or on paper were entered into the web-mounted database.

The survey was advertised in both the Aussie Times and the Australian Shepherd Journal and heavily promoted on breed discussion lists and via ASHGI’s international club contact list.

This survey was intended for purebred Australian Shepherds born from 1990 through 2005. The birth date range was selected to ensure that we had data on dogs that were old enough that a fair amount would already be known about their health status and to include some whose life cycles were complete.

Our overriding goal was to obtain data that would allow us to gauge the frequency of various health and genetic issues in the breed. We also sought more detailed information on each item which will help us in our educational efforts on behalf of the international Australian Shepherd breed community.

This report contains discussion and analysis of the overall data set. We hope in the future to take a more detailed look at subsets of the data focusing on particular health or genetic issues, classes of disease (e.g. eye, orthopedic, etc.) or other topics of interest.

Who Responded

375 individual owners submitted data on 612 dogs. We also received data on approximately 100 more dogs that did not meet the survey criteria. Data from the out-of-criteria entries has been retained for future study and investigation of specific areas of interest but will not be reflected in this report.

The survey was truly international in scope, with submissions received from 17 countries. 35% of the entries came from outside the US. 28 Aussie owners in the Netherlands represented the largest non-US group, with Germany, Canada, Norway, and the United Kingdom also well-represented. For a full list of participating countries, see Figure 2.

| Fig 2: Participating CountriesNumber of owners responding given in parentheses | |

| Australia (7) Austria (1) Belgium (3) Canada (20) CzechRepublic (1) Denmark (2) Finland (9) France (5) Germany (21) |

Netherlands (28) Norway (16) Slovenia (4) South Africa (1) Sweden (1) Switzerland (3) United Kingdom (11) United States (242) |

Within the US, we received submissions from 42 states. California (39 owners) was the most-represented individual state and was part of the best-represented region of the country. For a full regional breakdown see Figure 3.

| Fig 3: US Regional Participation | |

| Region | # Owners |

| New England (CT, MA, ME, NH, RI) Mid-Atlantic (MD, NJ, NY, PA) South (AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, NC, SC, TN, TX, VA, WV ) Midwest (IA, IL, IN, MI, MN, MO, NE, OH, WI) Mountain West (AZ, CO, ID, MT, NM, NV, UT, WY) Pacific (AK, CA, OR, WA) |

11

32

59

43

29

68

|

Note: No responses were received from states not listed above.

Most participants were experienced Aussie owners. 70% had been involved in Aussies between six and 20 years and another 16% in excess of 20 years. The depth of knowledge such people have to offer can only reinforce the value of the data collected by this survey. 80% had one to five Aussies and about 45% had one or more dogs that were not Aussies.

Aussies are dogs that want something to do and they attract people who enjoy doing things – all kinds of things – with their dogs. [See Figure 4]

| Fig. 4: Activities # of owners who are or were active indicated in parentheses. |

|

| Agility (281) Obedience or Rally (280) Stockdog/Herding Trials (154) Conformation (127) Tracking (103) Therapy (90) Commercial farm/ranch work (39) Flyball (32) Search and Rescue (32) Disc Dog/Frisbee® (26) Freestyle/Dog dancing (14) |

Dock diving/Water sports (10) Equestrian activities (6) Hiking & wild country activities (6) Winter sports (4) Assistance (service) dog (3) Field trials or training/gun dog (3) Lure coursing (3) Schutzhund/IPO (3) Trick dog (3) Weight pull/carting (3) Miscellaneous (12) |

38% of the respondents were breeders, not quite half of them having bred five or fewer litters. Slightly more than half stated that, on average, they bred less than one litter a year, 16% bred one or two litters per year and the remaining 30% didn’t respond to the question.

We decided to include a check-off box requesting permission to incorporate survey data in ASHGI’s IDASH Pedigree Analysis Database. Frankly, we had no idea how many people might be willing to do so and expected only a modest number of responses. To our delight and surprise, over three quarters of the participating dog owners were willing. Even for those participants who did not check the box, their willingness to complete the survey made this the largest general health survey in the breed to-date and the second largest Aussie health survey of any kind. (ASCA’s 2010 kidney disease mini-survey garnered over 1400 responses.)

The Dogs

The vast majority of the dogs (92%) were studbook registered and 40% of the unregistered dogs were out of registered parents. ASCA was the most represented registry with the American Kennel Club (AKC) a close second. Non-US registrations roughly mirrored owner participation, with Canada, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Norway leading the list. Multiple registrations remain the norm in Aussies; over three quarters carried papers with more than one registry, including 37% of the out-of-US dogs which carried ASCA papers along with those of their national kennel club. For detail on registries represented, see Figure 5.

| Fig 5: Registries Represented # dogs in parentheses |

|

| American Kennel Club (339) American Stock Dog (1) Australian National Kennel Club (12) Australian Shepherd Club of America (412) Austrian Kennel Club (1) Belgian Kennel Club (4) Canadian Kennel Club (37) Continental Kennel Club (2) CzechRepublic Kennel Club (3) Danish Kennel Club (3) Dutch Kennel Club (36) |

Finnish Kennel Club (14) French Kennel Club (11) German Kennel Club (12) The Kennel Club – UK (27) National Stock Dog (4) Norwegian Kennel Club (19) Slovenian Kennel Club (5) South African Kennel Club (1) Swedish Kennel Club (1) Swiss Kennel Club (1) United Kennel Club (29) |

| Note: Names of kennel clubs in countries where English is not the primary language are approximated. | |

Our Aussies are globe-trotters. Fully 10% had changed country of residence at least once. A quarter were exported from the US or Canada to other countries but almost half of those who moved did so between countries outside North America. A few came home from those countries to the US.

The survey included 301 males and 311 females. 61% were altered but 22% of those had been breeding dogs. The most frequently cited reasons for altering were personal preference, medical/health issues, breeding retirees, and not breeding quality. Among the dogs which had been bred, 45% were altered when retired.

Average height of the dogs was 20.6” (52.6cm.) Average weight was slightly over 48# (21.6kg.)

88% of the dogs were either bred by the owner or obtained from the breeder. 6% came from rescues or shelters and the balance from a variety of other sources. 84% were obtained under 6 months of age.

Lifestyle

Environmental issues can impact health, so we also requested information on a variety of lifestyle topics.

Diet

The most frequently used feed was commercially produced kibble, fed to 87% of dogs. Home-prepared raw was the second most common diet (16%) followed by commercially-produced raw (11%) and commercial canned food (8 %.) 35% of the dogs received treats and 12% got table scraps. Just over half regularly received supplements, the most frequent being joint supplements (64 %,) vitamins/minerals (50 %,) fish oils (27 %,) and herbals (22 %.)

Housing

92% of the dogs were either primarily house dogs or spent a substantial part of their time in the house. 64% lived in multi-dog households with no more than 5 dogs total while only 10% were single dogs.

Training

75% of the dogs attended puppy classes. 85% were trained in various performance/working areas, reflecting the varied activity interests of their owners. 51% had been trained for the conformation ring.

99% of the dogs whose early history was known by their owners received puppy vaccinations and 94% were vaccinated as adults. For 43% the owners indicated they had reduced the number and/or frequency of vaccinations, 21% were kept to the same schedule, and 10% were no longer vaccinated at all though some of these were elderly.

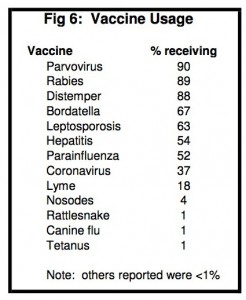

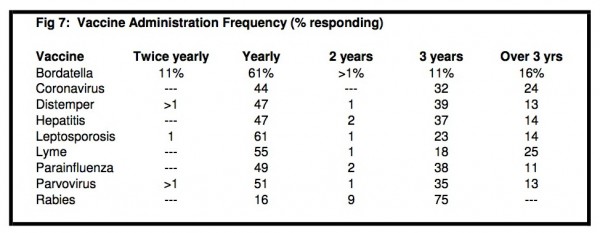

38% of owners said they stopped vaccinating at a certain age. 44% of the dogs whose owners did so were stopped at 10 years or greater and another 28% from 7 to 9 years, though this leaves a significant minority who received no vaccines through most of their lives. Usage of specific vaccines varied [see Figure 6] as did frequency of administration [see Figure 7.] Only 4% gave their dogs nosodes (homeopathic vaccines.)

Rabies is the only vaccine that is legally required in some jurisdictions. 63% of the dogs were administered rabies vaccine according to local law. Well under 1% of those in rabies-mandatory locations failed to vaccinate their dogs while 71% of the dogs who lived in places where rabies was not mandatory received the vaccine, though to some extent that may have been because the dogs traveled across state or national borders.

Rabies is the only vaccine that is legally required in some jurisdictions. 63% of the dogs were administered rabies vaccine according to local law. Well under 1% of those in rabies-mandatory locations failed to vaccinate their dogs while 71% of the dogs who lived in places where rabies was not mandatory received the vaccine, though to some extent that may have been because the dogs traveled across state or national borders.

5% of the dogs suffered veterinarian-diagnosed vaccine reactions. Rabies vaccine caused the most reactions (44%). Other vaccines indicated each caused roughly the same amount of reactions but at most less than a third as many as rabies. The most common type of reaction was swelling (65%).Rabies is the only vaccine that is legally required in some jurisdictions. 63% of the dogs were administered rabies vaccine according to local law. Well under 1% of those in rabies-mandatory locations failed to vaccinate their dogs while 71% of the dogs who lived in places where rabies was not mandatory received the vaccine, though to some extent that may have been because the dogs traveled across state or national borders.

23% of owners used titers with the majority using them only once or at long (3-5 years) intervals.

Alternative Medicine

35% of the dogs at some time received alternative or holistic medical treatment. See Figure 8 for the types of treatment received.

| Fig 8: Alternative/Holistic Treatment Usage | |

| Type |

% Dogs Receiving

|

| Chiropractic |

66%

|

| Massage Therapy |

56

|

| Homeopathy |

45

|

| Acupuncture |

32

|

| Flower Essences |

32

|

| Western Herbs |

17

|

| Chinese Herbs |

15

|

| Essential Oils |

14

|

| Reikei |

13

|

Toxic Exposures

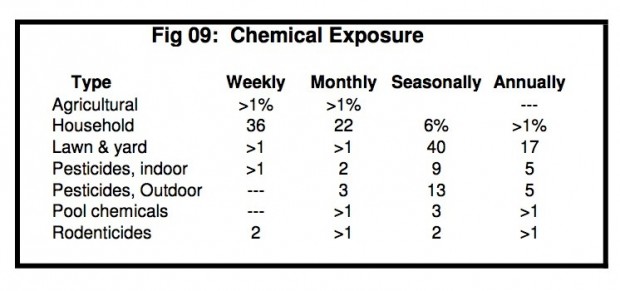

We asked about exposure to various commonly used chemicals which are potentially toxic. [See Figure 9]

Health Screening

Screening for eyes, hips and, to a lesser degree, elbows have been long-standing practices in the breed. 71% of dogs had had their hips screened and 32% had elbows checked. We did not specifically ask about eye screening, however, the great majority of affected dogs were diagnosed by veterinary ophthalmologists rather than small animal clinicians or the owner.

DNA testing has become commonplace, based on statistical information acquired from the various testing labs. However, this type of test has only been available for Aussies for a few years so many of the dogs in this survey would never have had the opportunity for testing and only the MDR1 test would be likely to be given to non-breeding dogs. 36% of the dogs were reported as having had the MDR1 test. The second most utilized test was for HSF4 cataracts (19%). 8% were tested for Collie Eye Anomaly. No one reported using any other DNA screening tests.

Health Issues

12% of the dogs were rated by their owners as having generally fair or poor health. When asked at what age the dog’s health began to decline, half said between 3 and 8 years and a 28% said 10 years or older. The older group is reflective mostly of the age of the dogs while the younger illustrates that most of our breed’s health problems arise in the prime of adulthood.

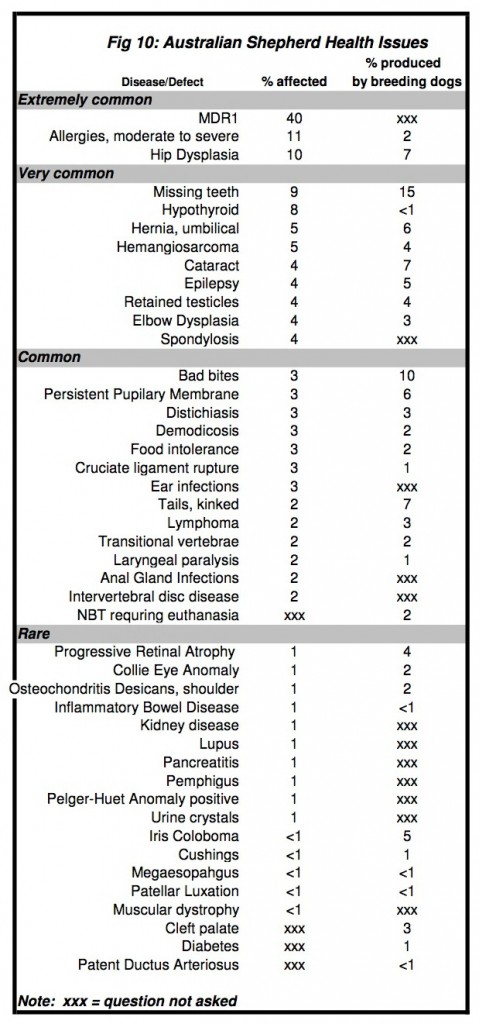

We asked about a long list of specific health issues. [See Figure 10]

We asked about a long list of specific health issues. [See Figure 10]

Something to keep in mind when reviewing this chart and other survey data is that surveys of this kind cannot sample a random selection of individuals; data will tend to be skewed to some degree. One obvious example is that dogs which died young are unlikely to be submitted and those that die very young aren’t submitted at all. Most of the respondents have had Aussies for many years but only 39% of them submitted multiple dogs. Because of the length and detail of the survey, we suspect many respondents submitted those dogs they felt were most significant and what constituted significance likely varied widely from one respondent to another. Where better sources are available (e.g. Canine Eye Registration Foundation – CERF – statistics or cumulative results on frequently used DNA tests) these should be relied upon as more accurate indicators of frequency in the breed.

However, even with these caveats, so many different health and other issues were covered in the survey it is unlikely that any one item is grossly over or under represented.

The chart has been subdivided into categories based on the percentage of responses per item. For most items questions were included both for the dog itself and, if it was bred, whether any offspring were affected. Items which received no responses are not listed here.

Extremely common health issues (10%+ affected)

The health issue most frequently reported was the MDR1 mutation. 40% of the dogs had at least one copy of the mutation. As high as this is, it is understated: WashingtonStateUniversity has informed us that fully half of Aussies have at least one copy. Owners need to keep in mind that even dogs with a single copy can react to certain medications. While this mutation is not, in and of itself, a reason not to breed a dog – even a dog with two copies – the presence of the MDR1 mutation should be viewed as a fault and, over the long term, breeders should work toward reducing the its frequency in the breed.

We were surprised by the double digit results on the other two extremely common health issues, allergies and hip dysplasia. Minor allergies can arise in any individual given a long enough life, so the percentage in Figure 10 represents those that were rated moderate to severe by the dog’s owner. We should also note that allergies are one of those things people tend to self-diagnose, for themselves as well as their dogs. 23% of the dogs that were reported with allergies, including those with moderate or severe allergies, were not diagnosed by a vet so the actual number might be somewhat lower than survey results indicate.

The hip dysplasia number is about twice the frequency at which the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) reports HD in Aussies. However, an unknown number of dysplastic dogs’ x-rays are never submitted to OFA so we suspect the actual frequency lies somewhere between the two. Both allergies and HD can have significant quality-of-life impact for the dog and put a financial burden on the owner.

Very Common Health Issues (4-9%)

Of the nine health issues in this classification one, spondylosis, is unlikely to be inherited. It is a degenerative condition most likely to be found in older dogs. The frequency reported here probably reflects our Aussies’ active lifestyle.

At the top of this list – another surprise for us – is missing teeth. Not only were 9% of the dogs in the survey missing teeth, but 15% of the breeding dogs had produced offspring with missing teeth. This level of frequency in a breed which is supposed to have a full complement of teeth is a reason for concern.

Two other surprises in this category are umbilical hernia (5%) and retained testicles (4% of males.)

Hypothyroid disease (8%) is frequently autoimmune and therefore inherited, though some cases – particularly those arising in elderly dogs – may not be.

Elbow dysplasia (4%) screening is common if not expected in Europe, but not so in North America. Given that, the actual percentage of affected dogs might be higher than indicated here. Both thyroid and elbow screening are mandatory exams for certification by OFA’s CanineHealthInformationCenter (CHIC.) Their presence in the “Very Common” section of this listing is a good indication of why and we urge those who have breeding dogs to get this screening done.

We have known for some time that some items in this section – cataracts (4%), epilepsy (4%), and hemangiosarcoma (HSA – 5%), are frequent health issues in the breed. We lack DNA screening tests for epilepsy or HSA, so breeders must continue to rely on information exchange and pedigree analysis to limit risk. The HSF4 test, which targets the mutation associated with 70% of our breed’s inherited cataracts, was released in 2008 and has been widely used but will have had little impact on the dogs in this survey because of the birth date range. Hopefully, by the next time a general health survey is done, we will see reduced numbers of cataracts.

Common Health Issues (2-3%)

2-3% might not seem like much, but the reader should bear in mind that if a disease is inherited via a recessive mutation, this level of affected individuals in a population indicates 24-29% of the breed are carriers. If multiple genes are involved the numbers might be much higher.

The presence of many of these items won’t be much of a surprise to those who have been following Aussie health issues for any length of time, but some warrant comment.

Bad bites (including overshot, undershot, wry, and anterior cross-bite) top the “common” list. Bite faults were the only thing other than missing teeth to have a double-digit percentage for having been produced by breeding dogs.

We want to note that all of the dogs with Persistent Pupilary Membrane (PPM) had the iris-to-iris form which does not significantly impact vision and will pass CERF. CERF statistics indicate that only about one in 50 Aussies with PPM have the more serious lens or corneal attachments which will not pass and are potentially blinding. These more serious forms are sufficiently rare that it isn’t surprising that none were reported in a survey of this size.

Cruciate ligament ruptures and inter-vertebral disc disease may be additional reflections of our dogs’ activity level. However we want to make a cautionary note regarding cruciate ruptures: There is growing evidence that these may result from immune-mediated inflammation and therefore may have a genetic component.

We are not aware of Aussies with transitional vertebrae having any difficulties because of the condition. However, for some breeds – especially those with screw tails like the English and French bulldogs – they are problematic. Because of their frequency, Aussie breeders might want to play it safe by not breeding affected dogs to each other.

Anal glad infections can arise for a variety of reasons. If a dog’s glands are emptied regularly its risk of developing infection is significantly reduced.

Laryngeal paralysis is a disease of old and elderly dogs. It can severely impact quality of life and can be life-threatening. We have received reports of multiple cases of this disease in families, indicating that it may be inherited.

NBTs requiring euthanasia were included in the “Common” section because 2% of the breeding dogs were reported to have produced puppies with NBT-related birth defects severe enough to require euthanasia. Since NBTs with severe defects (hindquarter paralysis, spina bifida and other closure defects of the lower spine and groin) are euthanized very early in life we did not expect to find any affected individuals among the dogs submitted to the survey.

Rare Health Issues (1% or less)

Rare health issues, especially those with serious impacts on soundness or health, deserve attention. Any one of the items that can be inherited (most of those listed) could become common by the time of the next survey if they aren’t given sufficient attention by breeders or should some popular sire happen to carry genes for them.

Collie Eye Anomaly and iris coloboma, which at the time of the 1999 ASCA survey were common now fall into the rare category, probably because breeder awareness of these two eye diseases – one with a long-known mode of inheritance and the other something that does not require special testing to identify – enabled them to make informed breeding choices that reduced their frequency. Progressive Retinal Atrophy, identified a few years ago to be the progressive rod-cone degeneration (prcd) form, remains rare. However, reports of prcd/PRA have increased somewhat so it bears watching. Fortunately, a DNA test is available, as well as one for CEA.

Some other rare items warrant mention. 1% of dogs were reported to be affected with some form of kidney disease. Most cases either were or, from the descriptions offered, might have been juvenile renal dysplasia (JRD) which is inherited. JRD is a very serious disease which will shorten a dog’s lifespan if it doesn’t kill it outright. The results of ASCA’s 2010 Kidney Disease Mini-Survey also support this supposition.

Cushing’s disease is known to be inherited in some breeds and has been diagnosed in related Aussies.

Urine crystals also showed up in 1% of the dogs. There are two different forms: Uate and struvate. Urate crystals are known to be inherited. There is a DNA test for this type but as of this writing it isn’t known whether that mutation occurs in Aussies.

Because of the hereditary potential of several of these rare diseases, as well as the significant health impacts of a few of them, breeders need to make note when cases arise and avoid breeding dogs with affected relatives to each other.

Extremely Rare Health Issues

A variety of health problems were reported in only one or two dogs among the 612 in he survey. Those issues are not included here because the numbers are too small to be considered significant at this time. There were other health concerns occasionally reported in the breed which were listed in the survey but received no responses. Those have been omitted in this report, also.

Breeding History and Reproductive Issues

41% of the dogs had been bred (29% of males, 49% of females.) Males produced 1684 offspring in 239 litters and females produced 1177 in 200 litters.

12% of males and 26% of females had been Brucellosis tested with 41% of the females and 20% of the males being tested each time they were bred. 36% of the breeding males and 52% of the breeding females were bred to Brucellosis-tested mates.

4% of breeding dogs produced puppies that failed to thrive and the same percentage produced fading puppies.

Male reproduction

91% of litters produced by breeding males resulted from natural breedings of 76% of those dogs. 34% were bred to only one bitch naturally and an additional 54% to two to five bitches, with 66% covering the bitches two or three times. Average litter size was 7.62 pups.

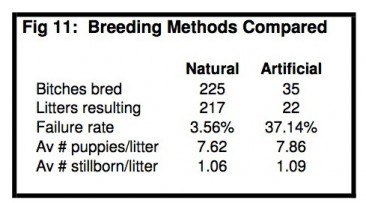

23% of the studs were used for artificial insemination, 65% with fresh semen, and 60% of them with a single female. None were artificially bred to more than 4 bitches. 22 litters resulted, averaging 7.86 puppies. For a comparison of breeding success between natural and artificial breedings see Figure 11.

23% of the studs were used for artificial insemination, 65% with fresh semen, and 60% of them with a single female. None were artificially bred to more than 4 bitches. 22 litters resulted, averaging 7.86 puppies. For a comparison of breeding success between natural and artificial breedings see Figure 11.

While the average number of puppies per litter isn’t significantly different, the breeding failure rate is. Among the matings reported in the survey, an artificial breeding was more than ten times as likely to fail.

The most common male breeding problem cited (17% of breeding males) was sterility, but most of these dogs were 10+ years old when they became sterile. After that, the most common was retained testicles (4% of males.)

Female reproduction

86% of litters from breeding females in the survey resulted from natural breedings. 17% of the bitches who delivered litters required at least one C-section. Average litter size for females was 6.22, with less than one puppy on average being stillborn. The average number of puppies raised to weaning per litter was 5.88.

Over a quarter of bitches had some kind of physical, behavioral or medical reproductive problem and 3% had multiple issues. The most commonly reported problems were requiring C-section for delivery (17%), damaging puppies (7%), and never able to conceive (3%). In a typically athletic breed with a normal canine body morphology this is a significant reason for concern.

Mortality

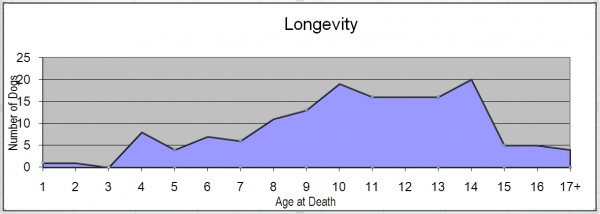

The birth date range for the survey was chosen, in part, so that some portion of the dogs would already be deceased. 25% were reported as no longer living at the time of the survey. The average lifespan for the dogs on which we had both birth and death dates was 10 years 10 months. The longest reported lifespan was 18 years 7 months and the youngest to die was 1 year 9 months. [See Figure 12]

However, dogs which die very young tend not to be reported in a survey of this kind. 73% of the deceased dogs were euthanized.

By far the most frequently indicated cause of death was illness, followed by old age and accident/trauma. 58% of those who died of illness had cancer and half of those had either hemangiosarcoma or lymphoma, closely resembling the results of the 2007 ASHGI Australian Shepherd Cancer Survey.

Very few (12%) deceased dogs were necropsied.

Behavioral Issues

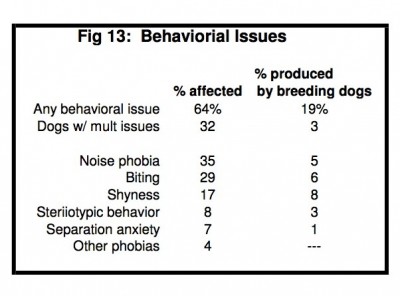

Sadly, 64% of dogs were reported as having some kind of behavioral issue. Half of those exhibited multiple issues. Almost 10% had relatives known to have similar behavioral problems. In addition, one breeding dog in five was reported as having produced puppies with behavioral issues. For a more detailed look at specific behavioral problems see Figure 13.

The most frequently reported issue, noise phobia, is known to be highly heritable. The other things reported may or may not be. Biting (humans or other dogs) was the second most common issue reported. 13% of dogs had a serious biting issue (multiple incidents at least one of which broke the skin) with other dogs and 3% with humans. Given the public’s understandably negative view of dogs that bite and the very real financial liability risk they pose, this figure is a reason for concern not only for breeders, but anyone training or owning Aussies.

The most frequently reported issue, noise phobia, is known to be highly heritable. The other things reported may or may not be. Biting (humans or other dogs) was the second most common issue reported. 13% of dogs had a serious biting issue (multiple incidents at least one of which broke the skin) with other dogs and 3% with humans. Given the public’s understandably negative view of dogs that bite and the very real financial liability risk they pose, this figure is a reason for concern not only for breeders, but anyone training or owning Aussies.

Breed Phenotype Issues

Coat Color

25 % of the breeding dogs were reported to have produced color faults, the most frequently reported, at 13% each, were excess white (in other than double merles) and dilution spots in merles. Two disqualifying colors occurred frequently enough to deserve mention: Full (“D-locus” or “maltese”) dilute (3%) and yellow/gold (2%). [See photos]

Interestingly, 1% were reported as brindle. For a dog to be a true brindle it must also be yellow, so a significant portion of dogs that carried yellow also carried brindle indicating that it is likely very common in the breed in general. The brindle pattern is caused by a different gene than yellow. Brindle cannot be detected at all in dogs that do not have tan trim and is often unrecognized in tan-pointed Aussies because of the variation allowed in tan points.

Tails

In the US and Canada, Aussie tails are either docked or naturally bobbed (NBT.) NBTs can, upon occasion, be associated with other problems. Therefore, several questions were focused on NBTs.

Over a quarter of the dogs whose owners knew their tail length at birth stated the dogs were natural bobs. 53% of NBT dogs were reported as having “very short” or “absent” tails. When “short” tails that were docked are taken into account, somewhere between 16% and 26% of NBTs are short enough that docking would not be necessary under the ASCA and AKC standards.

3% of the dogs with known tail length had kinked tails. All but one of those were also NBT, indicating a strong association between NBT and tail kinks.

27% of dogs, including 80% of those outside the US, were not docked. Because of the international nature of the survey and the fact that many countries have instituted docking bans, the survey committee decided a section on tail conformation would help breeders in those countries determine what type of tail is typical in the Australian Shepherd. Since the breed traditionally has been docked breeders have not selected for any particular kind of tail. We asked about tail shape, carriage, and feathering. Illustrations [See Figures 14, 15 & 16]

Fig. 14 – Tail Shapes

were provided as a visual guide to the written options offered. 60% of the dogs with known tail shape had a slightly curved tail, with no other tail shape coming close. Typical tail feathering was also clear, with 62% having feathers profuse at the base and shortening toward the tip. However, responses to the tail carriage question were less definitive: 33% of the dogs typically carry their tails slightly below the topline, 22% slightly above, and 21% carried them low. The atypical types of carriage were high over the back and level with the topline (oddly, given that 55% carry them slightly above or below.)

Fig. 15 – Tail Carriage

Fig. 16 – Tail Feathering

Educational Opportunities

The survey results have highlighted a need for greater educational efforts, not only from ASHGI but from national club health committees as well as regional clubs. Information on disease diagnosis and treatment would be helpful to Aussie owners, while breeders would benefit from breeding recommendations and strategies to reduce frequency of health problems and unwanted traits.

Several specific areas stand out as prime targets for such effort. Topping the list are immune-mediated diseases, especially allergies and hypothyroidism. This class of diseases was common a decade ago and remains so today. While any individual may develop minor allergies, more serious or chronic reactions are genetically predisposed. The high frequency of hypothyroid disease reported in the survey indicates that more frequent use of available screening panels is warranted. Breeders also need to be aware that that the genetics of autoimmune diseases like hypothyroidism are complex and different types of autoimmune disease are frequently found in a single family. Therefore breeders need to approach these diseases as a single breeding concern rather than a plethora of separate diseases.

A variety of skeletal issues need to be emphasized. Hip dysplasia has not reduced in frequency over the past decade and may have increased. Elbow dysplasia is more frequent than most realize, requiring more diligent screening. Natural bob tails are also an area of concern, especially in those countries with docking bans; breeders should be strongly discouraged from breeding NBT to NBT not only because of the lethal risk to fetuses which inherit two copies of the gene but the potential for serious birth defects.

Some issues rarely hit many owners’ and breeders’ radar; laryngeal paralysis is a prime example. Not only does it seriously impact quality of life and longevity for older dogs, its late onset means it is impossible to prevent dogs that will become affected from being bred. However, tracking cases to identify dogs at risk and avoiding breeding them to other at-risk dogs could reduce frequency of this disease.

We were particularly troubled by the high number of behavioral problems reported, especially biting. While some specific issues, like noise phobia, are clearly inherited others may arise from environmental causes. Aussies are not for everyone; more emphasis is needed on proper socialization and placement.

The frequency of female reproductive issues should be a major concern for breeders. While things can go awry with any breeding and first-time moms may make mistakes, if a bitch requires medical intervention in order to be bred or to whelp she is not a good breeding candidate. Nor should aberrant behavior related to breeding or litter rearing be tolerated.

Many view missing teeth and bad bites as a minor concern, but the continued high frequency – and in the case of missing teeth, apparently increased frequency – of traits that are at best faulty and sometimes disqualifying points to a need for more stringent selection by breeders.

Hernias and retained testicles are other issues often dismissed as minor. From a medical standpoint, many of them are. However, their frequency is increasing. Retained testicles must be surgically removed and some hernias also require surgery. Breeders should be advised to avoid breeding dogs with a family history of these defects to each other.

Finally, the extremely high frequency of the MDR1 mutation in the breed highlights an increased need for education of owners about the importance of testing for all Aussies and, if the dog has the even one copy of the mutation, informing any veterinarian who treats it. Breeders should be urged to start breeding away from this mutation with a goal of significantly reducing frequency over the next several generations of dogs.

Future Plans

ASHGI intends to conduct more surveys of this type at intervals in the future. No date or specific plans have been made, but the next one will not be before 2015. The date-of-birth range for submitted dogs would be adjusted to accept data from dogs that were too young for the 2009-10 survey but who will be of suitable age at the time of any subsequent effort.