What you may not know about Aussies’ tails

by C.A. Sharp

Illustrations by Marja Tegelbeckers

![]() First published in Double Helix Network News, Winter 2014

First published in Double Helix Network News, Winter 2014

Many countries around the world have instituted bans on tail docking and other countries are giving serious consideration to doing so. In a breed like the Australian Shepherd where tails have traditionally been docked and are sometimes has naturally bobbed (NBT) this leaves breeders, clubs, and judges in countries where docking is no longer allowed asking, “What tail is correct?” The answer is: We don’t know. Nobody has selected for a particular tail conformation prior to the bans on docking.

The Survey

The Australian Shepherd Health and Genetics Institute (ASHGI) is concerned that different countries might independently decide on a “correct” Aussie tail. This risks fragmenting the breed gene pool if tail types are deemed “correct” or “faulty” depending on the country in which the dog resides.

From August 2009 through August 2010 ASHGI conducted a breed health survey which included questions specific to the conformation of tails as well as questions associated with NBT. The purpose of these questions was to provide breeders with information about NBT-related issues as well as help national breed clubs in countries where docking has been or may become banned determine what type of tail is typical in the Australian Shepherd.

The survey collected data on 612 purebred Australian Shepherd born within the survey birth date range of 1990 through 2005. Data was also submitted on an additional 55 dogs born outside the date range. While this non-compliant data was not considered in the official survey report it will be included here because the age of the dog does not influence the result of tail-related questions. Because of this larger data set some of the results here may vary slightly from those in the official survey report, however the expanded data set should yield more accurate results specific to tails than the official age-limited set. 35% of the survey entries came from seventeen countries outside the United States, mostly in Europe.

Natural Bob-Tails

28% of the dogs whose owners knew their dog’s tail length at birth stated the dogs were NBT. 51% of NBT dogs were reported as having “very short” or “absent” tails. When “short” tails that were docked are taken into account on US and Canadian dogs, a significant minority – perhaps as many as a quarter – of NBTs were apparently short enough that docking was not necessary to meet ASCA, AKC, and CKC standards. 39% of the breeding dogs in the survey were reported as having produced one or more NBT puppies. Only 26% of the NBT offspring were listed as having “short” or “absent” tails. These data vary considerably from those on the surveyed dogs, leaving some question as to what portion of NBTs are short enough to meet traditional length standards, but it is safe to assume that at the very least a significant minority do.

Breeders in countries with docking bans can expect that some of their puppies out of an NBT parent will have tails short enough to be consistent with the breed’s pre-ban appearance. However, a majority of NBTs will be longer and this fact needs to be considered when national clubs revise breed standards.

NBT-related defects

Defects associated with very short NBTs include spina bifida, closure failures of the perianal area, and varying degrees of paralysis in the hindquarters. 5% of the NBTs in the survey produced NBT offspring with defects which the owners indicated were sufficiently severe as to require euthanasia of the puppy. The defects occurred in 4%, or one out of 25, of the NBT puppies. It is probable that the other parent of these puppies was also NBT but the survey data so not provide this information.

Kinked tails

3% of the dogs with known tail length had kinked tails. 89% of the kinked tails were on NBT dogs and 16% of all NBTs – about 1 in 6 – had kinked tails. This indicates a strong – though not exclusive – association between NBT and tail kinks. There is also a possibility that some of the kinked tails which owners designated as “long” were actually longer-than-usual NBTs missing only a few vertebrae. NBT length did not appear to correlate with the frequency of kinks.

Tail conformation

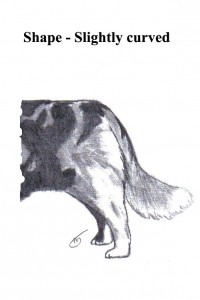

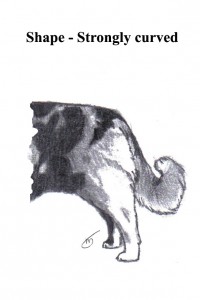

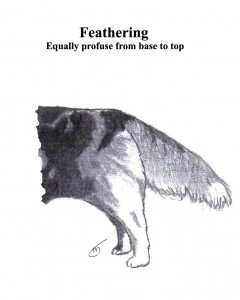

28% of the dogs, including 79% of those outside the US, were not docked. We asked about tail curvature, carriage, and feathering in order to determine what tail conformation is typical for the breed. Illustrations [See Figures 14, 15 & 16] were provided as a visual guide to the written options offered.

58% of the dogs with known tail shape had a slightly curved tail, with no other tail shape coming close.

Typical tail feathering was also clear, with 61% having feathers profuse at the base and shortening toward the tip. The data on offspring of breeding dogs conformed with the above.

Responses to the tail carriage question were less definitive. Owners indicated that 32% of the dogs and 24% of the offspring typically carry their tails slightly below the topline. 24% of the dogs and 28% of the offspring carry them slightly above the topline. 21% of dogs but only 12% of offspring carried them low. 21% of dogs and 23% of offspring carry their tails level with the topline. Carriage high over the back appears to be unusual. The highly variable answers to this particular question may be because dogs will alter their tail carriage in response to social interactions with other dogs or people. It is possible that respondents were unclear about the term “typical” as applied to tail carriage, misinterpreting social body language for the dog’s tail position when relaxed. But even with these muddy results, it is clear that very high and very low tail carriage are atypical.

What is Standard?

Despite the name, the breed originated in the western United States. The vast majority of US-registered Aussies have papers with the Australian Shepherd Club of America (ASCA) or the American Kennel club. Many dogs that are active in various types of competition or used for breeding have both. Docking remains the norm. The ASCA standard describes the tail as “straight, not to exceed four (4) inches natural bobtail or docked.” The AKC standard, from which most national breed clubs elsewhere in the world drew their own standards, was derived from the older ASCA standard and is largely similar and is essentially the same as regards tails: “Tail is straight, docked or naturally bobbed, not to exceed four inches in length.”

While these don’t address full tails they do give some guidance for breeders outside the US as regards kinked tails. Requiring that tails be straight implies that kinked tails faulty. Severity of the fault should probably be based on the degree of the kinking.

Naturally bobbed tails can come in a variety of lengths. They may be 4 inches (10.16cm) or less, but they may also be longer; sometimes much longer. Clubs in countries with docking bans need to determine whether longer natural bobtails are or are not acceptable and if not, how much they should be faulted. While longer NBTs are not terribly attractive, this is a strictly cosmetic concern. Heavily faulting such tails could encourage breeders to remove otherwise good quality individuals from the breeding pool. Doing so would not necessarily change the numbers of longer NBTs produced; little is known about the genetics of length variation in NBTs.

For long tails, the ASHGI survey indicates that the most typical tail is slightly curved with the length of feathering tapering from base to tip. Tail carriage appears to be variable though carriage that is either high over the back or very low are outside the norms. Breed standards should contain wording that addresses curvature and feathering of full tails. Minor deviations, like equal-length feathering along the length of the tail or a slight “hook” in the end shouldn’t be penalized too heavily. However, major divergence from the norm, as with a curled or completely straight tail or no feathering should be heavily faulted.

Tail carriage in any one dog can vary with mood and social interactions and the survey results were not clear enough to develop a description of “typical” carriage. Therefore, carriage should either not be mentioned in the standards or, at most, faults listed for tails held high and curled over the back or low and tucked under the hindquarters.

As a final word on standards, for the benefit of the breed it would be best if countries with docking bans came to some kind of consensus on wording that describes the tail so that what is and is not considered correct is uniform throughout the breed.

Breeding for tail type

The ASHGI survey found that when the tail length of the mate with which the dog produced NBTs was known 67% were NBT, indicating that breeders in countries with docking bans may be favoring NBT dogs for breeding in hopes of producing puppies with the traditional breed appearance. How successful this will be is unknown since so little is known about the genetics of the variation in NBT length. It also indicates that some breeders are mating NBT to NBT, though the survey data did not answer that particular question.

Breeding two NBTs together is unwise. Like merle, the NBT gene is dominant with serious defects associated with having two copies. These defects are so serious that most double NBT fetuses are reabsorbed. Breeding together NBTs with especially short tails – the sort that would meet US breed standards – may contribute to the severity of these defects. Reabsorbtion of defective fetuses can impact litter size and some puppies may be born with significant lower spinal defects which require euthanasia of the puppy.

Kinked tails rarely present any health or soundness issue for the dog but they are unsightly. They are also strongly associated with NBT. To reduce the frequency of kinks, dogs with kinks or which have near relatives with kinks should be bred to mates that have full tails and are from families where kinked tails are not known to occur as the genes for kinking may be entirely separate from the NBT gene.

Once formal consensus is established by way of breed standard revisions for the correct Aussie tail type, breeders should select toward the preferred tail. However, the appearance of normal full tails is a cosmetic issue and minor deviations should not be given precedence in selection over more substantive issues of structure, health, disposition, and performance or work attributes.

Coming to the point

The upshot of all this is that if your country does not allow docking, your national breed club should network with other national clubs in countries with similar laws to develop consistent wording about tails for your breed standards. You cannot look to country of origin standards to answer this question because docking remains standard practice among US Aussie breeders and both clubs adamantly oppose anti-docking legislation.

Once standards for tail appearance are developed, breeders need to take a common sense approach to how they prioritize what is – with the important exception of NBTxNBT matings – a cosmetic issue when making breeding decisions least the tail start wagging the breed.